It seems like every year around this time, I’m fighting misinformation on the god Lúgh. Everywhere one looks on the internet, people are perpetuating the same outdated stuff; that Lúgh is a sun god, and/or a god of the grain. The origin of such notions is from new age books that never bothered to research beyond outdated Victorian-era anthropology.

I mean, you only have look it up on wikipedia to know that his name doesn’t link him to the sun: “The exact etymology of Lugus is unknown and contested. The Proto-Celtic root of the name, *lug-, is generally believed to have been derived from one of several different Proto-Indo-European roots, such as *leug- “black”, *leuǵ- “to break”, and *leugʰ- “to swear an oath”. It was once thought that the root may be derived from Proto-Indo-European *leuk- “to shine”, but there are difficulties with this etymology and few modern scholars accept it as being possible (notably because Proto-Indo-European *-k- never produced Proto-Celtic *-g-).”

Some of the later new age publications actually acknowledge that modern scholars say Lúgh isn’t a sun god, but word it so as to not step on the toes of the die-hard sun theorists. The main passage that comes to mind is one published in Lammas: Celebrating the Fruits of First Harvest by Anna Franklin & Paul Mason, and has been copied onto Lúgh articles all over the internet. It states: “While some writers state, without hesitation, that Lugh was a sun god, others, with equal force, argue that he was neither a god of the sun nor harvest.” What the author seems to be doing here, is giving both ideas equal merit. However, they don’t have equal merit. The actual historical record speaks for itself.

There is no record of Lúgh being worshiped as a sun god, but ample evidence that both his name meaning and his roles in Celtic religion were something else entirely.

“…helped along by Victorian scholars’ obsession with “solar myths”, it was taken for granted that Lúgh was a solar god… However, traditional, ritual-associated ideas about Lúgh show no trace of this… Lugus has his domain in storm rather than in sunlight, and that if his name has any relation to “light” it more properly means “lightning-flash”… This is the principal function of his invincible spear…” –Lugus: The Many-Gifted Lord by Alexei Kondratiev

Why does it irk me so that the misinformation persists? Because people who think Lúgh is a sun god are getting the story wrong. Because if you’re getting the story wrong, then you’re also misunderstanding the meaning of an entire holiday; Lughnasadh. Because if you think Lúgh is a sun god, you do not know the real Lúgh. The real Lúgh is much more interesting and complex.

So that is why I’m writing this. It’s time to go beyond calling out the sun myth debacle, and move on to telling folks about his true character.

Excuse me, do you have a moment to talk about our lord and hero, Lúgh?

He was known by the continental Celts as Lugus, by the Welsh as Lleu, and by the Irish as Lúgh. We must look to all these cultures to get a complete picture of who Lúgh is. When Romans encountered Lugus, they equated him with their god Mercury, patron of travelers, commerce, trickery, and eloquence.

Early depictions of Lugus show him with a Tree of Life, twin serpents, dogs or wolves, birds (especially two ravens), horses, and mistletoe. He has similarities with Cernunnos, as they are both threshold gods, psychopomps, have a triple form, and a magical bag.

He has much in common with, and may actually be the prototype for- Odin. Like Odin, he wields a spear and is associated with two ravens. They are both psychopomp deities (again, like Cernunnos and Mercury). Both are travelers and magicians. Odin is god of wisdom, Lúgh of intellect and of every skill. Odin is one-eyed. Lúgh closes one eye to do magic on the battlefield. Odin was hung on a tree, pierced by his own spear, died and was reborn. So was Lleu. There are a few similarities with Loki as well, as they are both tricksters and associated with the mistletoe, however Lúgh is seen in a much more positive light than Loki. (For more of such comparisons, read The Birth of Lugh – Óðinn and Loki among the Celts by Thor Ewing, and Of Norse Loki and the Celtic Lugh.)

So if you know a little about Norse mythology, you may be starting to form a picture in your mind of some of the aspects of Lúgh’s character; imagine a younger, smaller, Celtic Odin (especially in his traveler guise), with a fair bit of the trickiness of Loki. Now imagine that like Thor, he can also wield lightning. He shares some strikingly similar characteristics and powers with these gods.

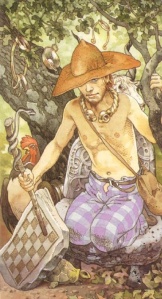

I think of all the modern day depictions of Lúgh in art, the Magician in Lo Scarabeo’s Celtic Tarot captures his spirit the best; the slender wiry god sits perched in his sacred oak (a tree sacred to several Indo-European thunder gods), a floppy red Odin-eske hat covering one eye, and his magic bag slung over his shoulder. The torc around his neck is huge (or is it the god that’s small?). He is surrounded by some of his symbolic animals (serpent, horse…). Torcs and rings of gold hang from the trees. A fidchell board (Celtic chess- his invention) lies at his knee.

In Irish lore, Lúgh was born of a Fomorian mother (Ethniu), and a Tuatha Dé Danann father (Cian). The Fomorians were an earlier race of beings that inhabited Ireland, sometimes depicted as monstrous giants, sometimes from under the sea. They represent wild chaotic nature. The Tuatha Dé were the race of divine beings that would later become the Sídhe, and were often represented as the gods of humanity and civilization.

Lúgh was born of both races, and so has a mastery of both nature and civilization, of the below and the above, of humankind and the divine. It is no wonder then, that his traditional places of worship are high hills with a nearby water source.

In the Battle of Mag Tured, Lúgh goes up against his own grandfather, the evil Fomorian king Balor. With his swift sling (or in folk tradition, his spear), he pierces Balor through his fiery poisonous eye (which represents the harsh summer sun). In winning this battle, he gains control of the land for the Tuatha Dé (and metaphorically saves the crops from scorching in the fields from Balor’s evil sun-eye).

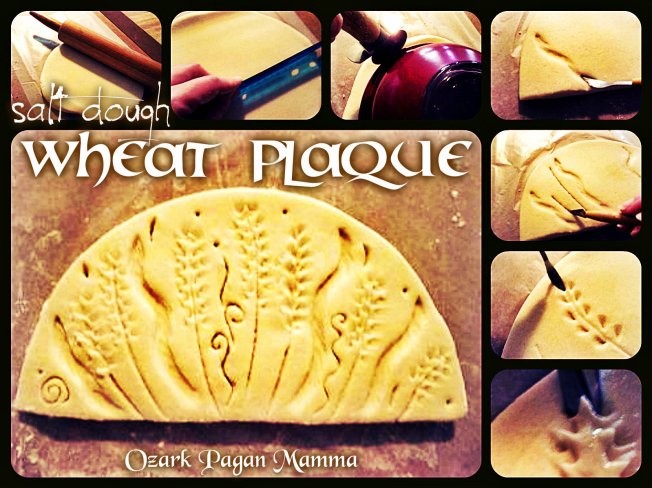

He was fostered by Manannán mac Lir, the sea god and gatekeeper to the Otherworld, and so has many water associations and inherited much of Manannán’s magic. He was also fostered by Tailtiu, a Fir Bolg queen who died clearing land for agriculture. And it was in honor of his foster mother Tailtiu that Lúgh instituted the first Lughnasadh festival and funeral games.

I have just hit a very few of the highlights here, describing some of the points in the mythology that tie in with the season of Lughnasadh, and describing some of Lúgh’s traits that I find especially interesting. I know I have left out a lot of important parts of his lore. Find more of the story of Lugh in Lebor Gabála Érenn (The Book of the Taking of Ireland), and The Second Battle of Mag Tured (Moytura). Read about Lleu in the Fourth Branch of the Mabinogion.

He is god of Land, Sky, and Sea. God to kings, warriors, and farmers. He is the quintessential underdog, surviving and winning despite the odds and with intellect and magic rather than brute force only. He is both hero and trickster and sovereign protector of the land. He is patron of travelers, for he travels with the lightning, small and swift, many places at once. He traverses worlds.

As Alexei said, “His many gifts remain at the disposal of those who trouble to seek him out.” Indeed, I hope you do.